Wildlife encounters often polarise people, none more so than the hugely popular Oslob Whale Sharks in the Philippines, where whale sharks gather en-masse to feed around fishing boats, and tourists gather en-masse to watch. Is this an unnatural, harmful experience for these giant creatures? And the surrounding marine environment. Or is it the opposite?

Myth-busting Oslob Whale Sharks

There are claims that by feeding the whale sharks, their behaviour is modified, the sharks stop migrating, further claims that the animals are often harmed by the close encounters. But marine scientist Judi Lowe claims otherwise.

Lowe, a marine scientist at the Southern Cross University in Australia, led a recently published study of Oslob Whale Sharks (OWS), together with Dr Mark Meekan and Johann Tejada at the Bureau of Fishery and Aquatic Resources.

“People say the feeding stops the whale sharks migrating, a common myth. There is no evidence for this at all. It’s also claimed the whale sharks are habituated to boats and people, and I’m not sure why this is problematic. The whale sharks of Tan-awan have been nudging fishing boats and nets of these fishermen and their fathers and grandfathers for generations.

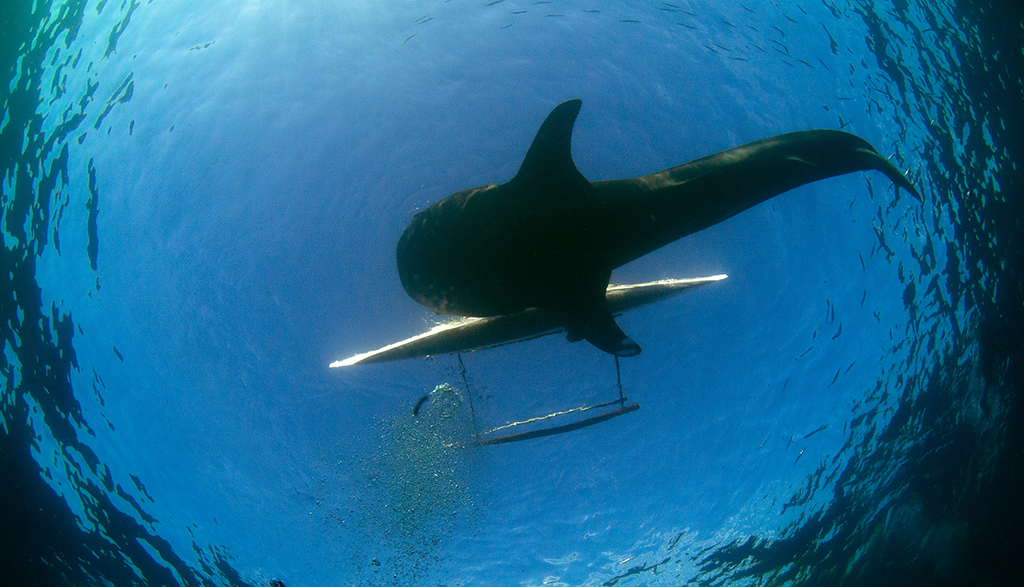

“As to damage done, the boats used to take tourists for an encounter are small non-motorised outrigger canoes, called banca – traditional fishing boats. No harm comes to the whale sharks from propellers, unlike pretty much every other whale shark swimming location around the equator. People also say that it is unnatural for whale sharks to spend time in shallow water and feeding upright is not natural behaviour. These statements are both wrong.”

Lowe’s research into Oslob Whale Sharks has found that these diving tours run by former fishermen have lifted local villagers out of poverty and given new protection to overfished marine life. The fishermen-turned-entrepreneurs have hit on a successful scheme to help lift their coastal community out of poverty, which also finances the protection of endangered whale sharks in the Philippines.

The History of Oslob Whale Sharks

Back in 2011, a group of 58 fishermen from Oslob who were struggling to feed their families turned to the local whale shark population and set up a community-based dive company. In a few short years it has become hugely popular, attracting more than 750,00 visitors in the first five years and amounting to $18.4m in ticket sales over the same period.

While the attraction has drawn criticism, Lowe’s research argues that this unique business model has improved food security, healthcare and education in the community while also safeguarding the species. Whale sharks are protected by law here, but illegally poached and finned alive in other parts of the country.

“Oslob, in the province of Cebu, is one of the poorest fishing sites in the Philippines but also anywhere in the world,” said Lowe. “Before the creation of OWS many of the fishermen could not afford to put food on their table or educate their children, some had also lost their homes in typhoons.”

Former fishermen Jesson Jumuad who leads a team at OWS said: “As fishermen, we were earning as little as $1.40 a day and nothing on days when the current was strong.

“Sometimes in a day I didn’t have any fish to be sold but now I can give my family good food three times a day. I have built a brick house, bought a motor bike and can afford to send my daughter to school.”

Overfishing and reef destruction

Historically, food security in Oslob has been an issue due to years of overfishing and the destruction of coral reefs. Between the 1950s and 1980s a destructive form of fishing called ‘muro ami’, was common here.

The practice of muro ami employed children, sending them underwater to form a human curtain, pounding the coral with rocks, to drive fish into nets. “They smashed up the reefs leading to diminished fish stocks, deepening the poverty of the fishing community in Oslob,” said Lowe.

Oslob Whale Sharks: a special connection

But the fishermen of Oslob never hunted the whale sharks. Their connection with the creatures spans generations. The fishermen knew how to lure them away from their nets with handfuls of krill should they bump into their canoes.

In 2011 a tourist paid one of these fishermen to attract a whale shark close to shore so he could get a proper look, and the idea of using whale sharks as a source of income was born. Now the local fishermen paddle tourists out to watch, snorkel or dive with the sharks 364 days a year from 6am to midday.

And the new-found income stays in Oslob, providing livelihoods, increased food security, healthcare, education and housing for the community while protecting the sharks and the coral reefs their livelihoods depend on.

Sixty percent of the business is owned by the fishermen, 10% by the local village of Tan-awan and 30% of the profits go to the local authority to fund marine wardens, employed to protect the region from poachers or those using destructive fishing practices.

The Philippines outlawed the hunting of whale sharks in 1998 but illegal poaching continues with the sharks’ fins exported and sold on the black market. As well as the protection of whale sharks, money generated funds the management of five marine reserves.

Lowe’s study found that while expatriate and national elite-owned dive tourism can undermine local livelihood benefits – the OWS model has shown how community dive tourism without donor funding can bring big payoffs for fishers and their communities. In addition, the business helps conserve the marine environment by reducing the fishing efforts of 177 fishermen.

Research investigating the physical impact of feeding the whale sharks, from the same team, in collaboration with a specialist whale shark scientist, is due to be published early next year.

Access the full report here: ‘Does provisioning for tourism harm whale sharks at Oslob? A review of the evidence and reply to Ziegler et al. (2018)’, co-authored by Judi Lowe and Dr Mark Meekan.