Most people believe that protecting our marine environment is essential to sustain ‘life as we know it’ on planet Earth. We all know that marine parks are important globally as well as locally. But with an issue this enormous, one that affects all of us, it is very difficult to figure out how best to address it.

Diveplanit presents an ‘explainer’.

In typical human style the problem of protecting anything starts with lines drawn on a map: this bit is ours and that bit is yours. Every country is allowed to draw a 200 mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) around its landmass – unless that runs into someone else’s EEZ, in which case they draw the line half way between the two.

What sits outside these land-grabs (or water-grabs) is termed the High Seas (seriously) and it amounts to about 64% of the oceans.

Pretty much everyone has the right to navigate and exploit the waters of the High Seas, and there is little to no protection of this environment. Any progress here will be made by the United Nations: a process is in place to draft elements of a treaty, and hopefully by September 2018, the UN General Assembly (UNGA) may convene an intergovernmental conference for finalising the treaty text.

What about the other 36%?

Surely the 36% that is directly under the control of sovereign states can easily be protected? Yes and no – it depends what you mean by protection.

Common Misconceptions

There is a common misconception that all Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are no-take or no-fishing areas. In many MPAs, only a small fraction has no-take status.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (- the folks who create the Redlist of endangered species), have 6 categories of conservation, but don’t have specific categories for marine conservation.

IUCN Class No. 2 is the one that most frequently applies: “National Park – protected area managed for ecosystem protection and recreation” (which often includes fishing).

Another misconception is that most MPAs are federally managed. Again, not true: they can exist in commonwealth, state, territory and tribal waters.

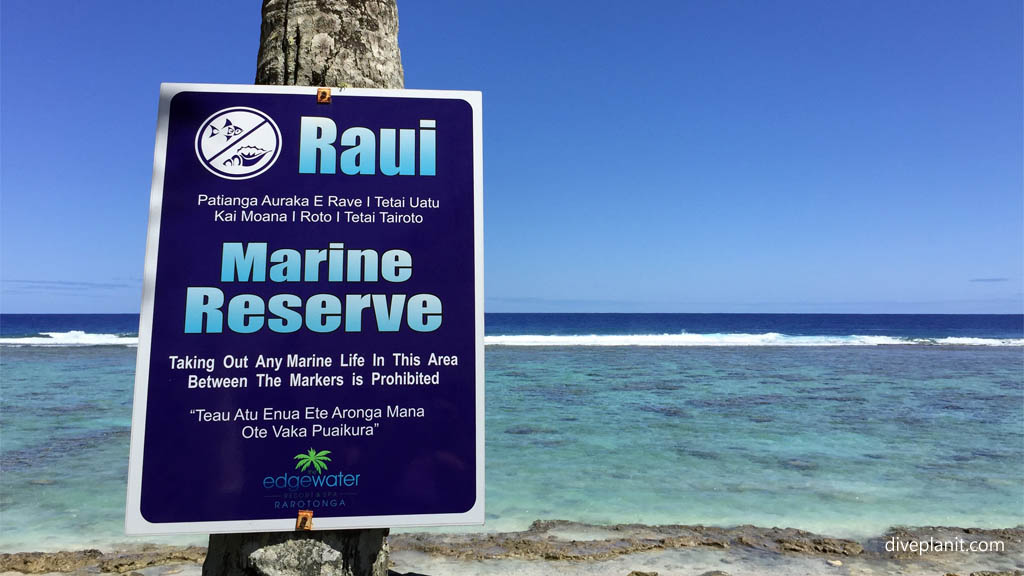

For example, there are areas in the Pacific in the Cook Islands and Fiji, which are declared by the local chief as ‘Raui’ or ‘Tabu’ – off-limits either long-term around an island resort to protect an area in the interests of tourism, or for a shorter period – to allow marine stocks to recover.

In terms of Protection – what makes an MPA successful?

Five Features of an MPA that make it successful: N.E.O.L.I:

- No-take – simply declaring an area a Marine Park and drawing a line on a map does not a sanctuary make!

- Enforced – if it’s not enforced it might as well not exist. It needs to be accepted by those who use it, and if necessary policed by locals or the local navy. (It is estimated that 20% of the world’s fish is still caught illegally).

- Old – old means at least 10 years – which in the grand scheme of things is not a long time. But it does mean that the sooner we declare, gazette and implement the protection, the sooner we will get the results.

- Large – ideally, larger than 100 square kilometres– which is the area inside a square 10km by 10km.

- Isolated – in so much as it comprises an ecosystem.

The key message is that it’s not the absolute size of the MPA, but the quality in terms of these factors of its protection that matters most. (And it doesn’t have to tick all boxes to be successful).

Looking at the Numbers

Around 2% of the world’s oceans are protected, and only 1% are strongly protected in no-take zones. So who’s doing well, who’s playing their part, and who’s dragging their feet?

Who’s doing well

Interestingly, the UK’s latest 834,000 km2 zone around the South Pacific Pitcairn Island provides the largest area of protection; which surpasses its Chagos Archipelago in the (disputed) British Indian Ocean Territory’s 544,000 km2.

Palau has declared 80% of its EEZ as a marine sanctuary – that’s around 500,000 km2.

Kiribati’s Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA) at 408,250 km2 is also one of the world’s largest, and that by a self-declared Least Developed Country.

Chile protected 297,000 km2 in 2015 around the Desventuradas Islands.

Many less developed nations like the Philippines and Malaysia are playing their part. Malaysia’s Tun Mustapha Marine Park in Borneo has just been gazetted covering an area of 10,000 km2 – which is big effort for a nation that needs the oceans to feed much of its population.

New Zealand is planning an MPA of 620,000 km2 around the Kermadec Islands, 1,000 km north of the NZ mainland.

The US is playing catch up as it still has only 1% of its waters protected despite Obama’s designation of the new Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument in 2014 at 1,236,000 km2 (A National Monument is a IUCN Type 3 MPA – some charter fishing, no commercial fishing allowed). But even the little US territory of American Samoa has 35,174 km2 of protected oceans.

How is Australia doing?

Our current government revoked a declaration of an additional 2.3 million km2 of Commonwealth Reserve to fulfil an election promise Tony Abbott famously made at a fishing expo, saying ‘more research is required’. The review was due to return findings by mid-2015. The last statement issued by the working group was over seven months ago in November 2015, with the lame apology that they’re still working on it.

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef MPA is 344,400 km2 but it’s an IUCN Class No. 6 – the lowest level of protection and only 4.6% of this is No-Take. So just 15,842 km2 of isolated patches on a reef 2,300 km long.

Let’s put that in perspective – Australia’s greatest tourism asset, the Great Barrier Reef, gets less than half the protection of American Samoa, a tiny spec in the Pacific Ocean.

Look a little deeper into the level of protection each bioregion of the Great Barrier Reef enjoys, and you’ll discover that the existing level of protection is incomplete or inconsistent and varying from zero to 62%. (That from the GBRMPA’s own website).

That’s why, unless we act now, it’s Stuffed with a capital S, underlined bold – to quote a recent phrase. So. Hands up everyone who wants to save the reef!

Of course we all do. So what can you do:

- Stay informed. There are a number of engaging and informative magazines and projects like: The Coral Triangle and National Geographic and locally Marine Explorer

- Advocate. There’s an election coming soon. Perfect time to get politicians of all flavours on record with some kind of commitment to hold them to post election.

- Put your money where your mouth is. Eat only sustainable seafood

- Donate. Think about it in terms of coffees or beers. Would you forego one coffee a week, or give the equivalent of a slab of beer for the reef to an organisation that is actually doing something about a key issue (ie, not just rising yet more awareness)? If so, click here.

- Volunteer. Organisations like Reef Life Survey need Volunteer Divers to collect the base data used by Scientists and Managers in Marine Research and Conservation. The GBRMPA needs volunteers to help kill off Crown of Thorns Seastars.

Most of all, do not lose hope. Most of the issues facing us have been recognised. Indeed many of the solutions have already been developed. We need the pressure of All of Us to drive the political will to make sure they get implemented.