A five-year study in Raja Ampat has confirmed that manta rays form friendships with other rays – and it’s the female rays that form the longer lasting relationships.

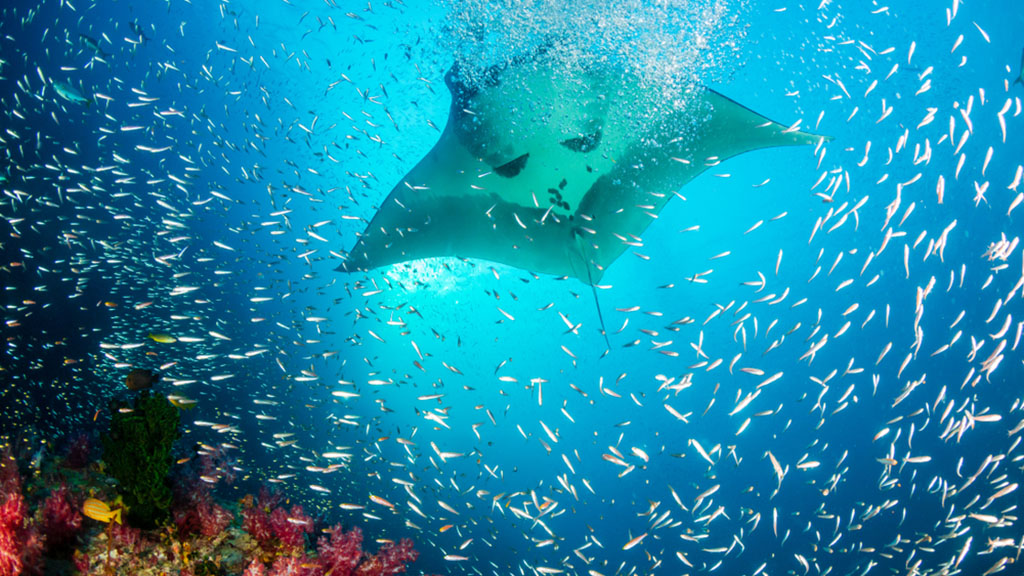

When it comes to marine encounters, most divers will include diving with mantas in their Top 5 diving experiences, their graceful movements often mesmerising – coming into close proximity with such a large, yet gentle creature can be magical to say the least.

But scientists are worried that their wide appeal is starting to disrupt natural behaviour. Combined with climate change, plastic pollution, fishing nets and fisheries that target them for their gills – prized in traditional Chinese medicine – it’s worried this increased popularity is threatening the species’ survival.

Macquarie University’s Robert Perryman set out with colleagues to research the mantas’ social structure to help predict their movements, mating patterns and response to humans to inform conservation and ecotourism.

“Social relationships are something that might be quite easily disturbed by human tourists who have good intentions but may inadvertently disrupt natural social behaviours,” Perryman explains.

Having previously collected data on mantas at a site in Raja Ampat, he had observed that the creatures exhibited group-like behaviours during feeding and courtship.

But whether that reflected active social preferences or occurred by chance due to habitat, feeding aggregations or seasonal migrations was unclear.

The team gathered data at several locations in Raja Ampat, while diving or snorkelling around cleaning stations or feeding areas. Individual rays were identified by the unique patterns of spots on their underbelly; like human fingerprints.

“They’re very curious and tolerant of humans, so it’s usually possible to identify all the individuals within a group during a 60-minute dive.”

From 500 samplings scientists recorded around 3,400 encounters, and by matching each photo to previous sightings they built up a database.

This enabled them to build a social network of relationships between rays that were seen at least 10 times, added to sightings recorded from photographs uploaded to a citizen science website. All up, sightings were taken from six sites spanning a 25-kilometre area.

The scientists were able to discern two distinct social communities within a very small area spanning around 15 km. One comprised mostly mature female rays and the other a mix of males, females and juveniles.

The older females formed longer-term associations, congregating together over weeks and even months. Males tended to form more casual acquaintances, with juveniles and mature males staying away from each other.

This social behaviour wasn’t entirely unexpected. “From their large brains we expect them to be reasonably intelligent animals.”

By understanding their behaviour, researchers hope to achieve the right balance between species preservation and ecotourism.

“Knowing how mantas interact is important, particularly in areas where they are susceptible to increasing dive tourism,” says Andrea Marshall, co-founder and principal scientist at the Marine Megafauna Foundation.

“The increasing number of boats and scuba divers around reef mantas in Raja Ampat, particularly at cleaning stations, could break apart their social structures and have impacts on their reproduction.”

Researchers hope this new information will help conservation efforts by encouraging broader respect and compassion for these graceful sea creatures.