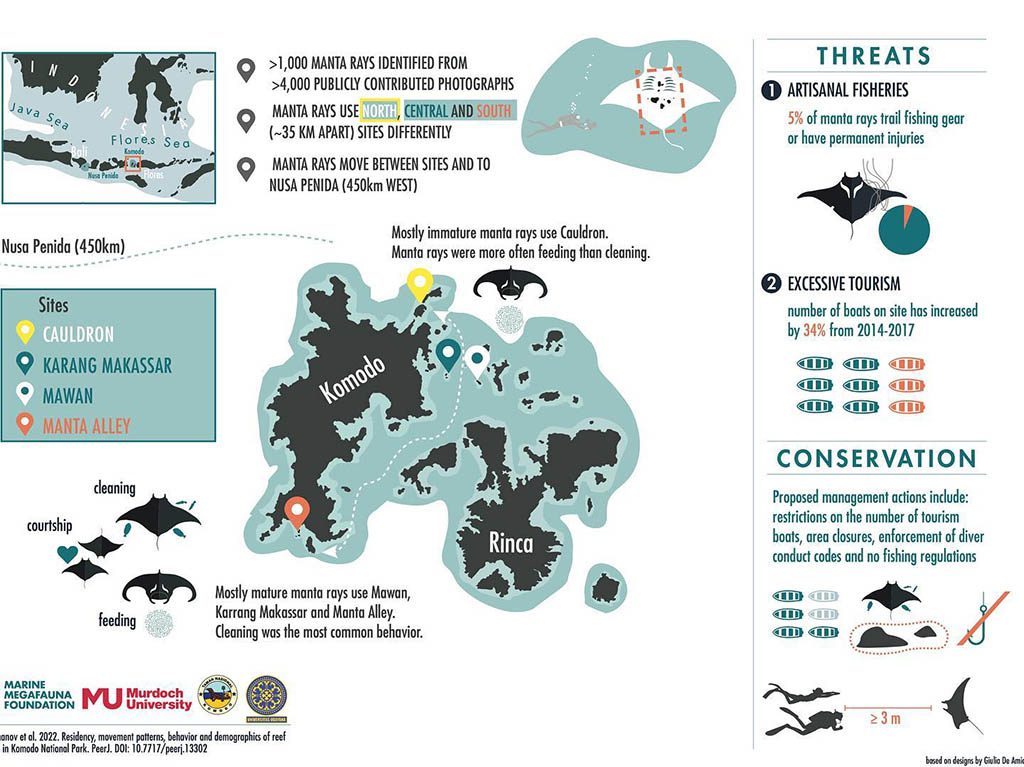

A new study conducted over several years in Komodo National Park, with over 4000 manta sightings uploaded by citizen scientists, reveals just how important the protection of waters within Komodo National Park really is.

A collaborative effort between citizen divers, scientists from the Marine Megafauna Foundation (MMF), and Murdoch University, reports a large number of manta rays in the waters of Komodo National Park, Indonesian, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, suggesting the area may hold the key to regional recovery of the threatened species.

1085 individual mantas were identified in the survey, with 95 per cent of data contributed by citizen scientists – divers and snorkelers visiting the region between 2013 and 2018.

Reef mantas (Mobula alfredi), which grow up to 5m, tend to reside and feed in shallow, coastal habitats. They also visit ‘cleaning stations’ on coral reefs to have parasites, or dead skin picked off by small fish. Courtship ‘trains’ are also observed adjacent to cleaning stations. In Komodo National Park, manta rays are present year-round, challenging the famous Komodo dragon as the most sought-after megafauna for visitors.

Scientists teamed up with the dive operator community to source identification photographs of manta rays visiting the parks’ waters and submit them to MantaMatcher.org – a crowdsourced online database for mantas and other rays. Most of the photographs came from just four locations from over 20 commonly visited by tourism boats.

“I was amazed by how receptive the local dive community was in helping collect much-needed data on these threatened animals,” said lead author Dr. Elitza Germanov. “With their support, we were able to identify over 1,000 individual manta rays from over 4,000 photographs. ”

“People love manta rays—they are one of the most iconic animals in our oceans. The rise of the number of people engaging in SCUBA diving, snorkeling, and the advent of affordable underwater cameras meant that photos and videos taken by the public during their holidays could be used to quickly and affordably scale data collection,” said MMF co-founder and study co-author Dr. Andrea Marshall.

The photographs’ accompanying time and location data is used to construct sighting histories of individual manta rays, which can then be analyzed with statistical movement models. These models predict the likelihood that manta rays are inhabiting or traveling in between specific sites. The study’s results showed that some manta rays moved around the park and others as far as the Nusa Penida MPA (>450 km to the west), but overall, manta rays showed individual preferences for specific sites within the Park.

“I found it very interesting how some manta rays appear to prefer spending their time in some sites more than others, even when sites are 5 km apart, which are short distances for manta rays,” said Dr. Elitza Germanov. “This means that manta rays which prefer sites where fishing activities continue to occur or that are more popular with tourism will endure greater impacts.”

Fishing activities have been prohibited in many coastal areas within Komodo NP since 1984, offering some protection to manta rays prior to the 2014 nationwide protection. However, due to illegal fishing activity and manta ray movements into heavily fished waters, manta rays continue to face a number of threats from fisheries. About 5% of Komodo’s manta rays have permanent injuries that are likely the result of encounters with fishing gear.

The popularity of tourism to these sites grew by 34% during the course of the study. An increase in human activity can negatively impact manta rays and their habitats. In 2019, the Komodo National Park Authority introduced limits on the number of boats and people that visit one of the most famous manta sites.

“This study shows that the places where tourists commonly observe manta rays are important for the animals to feed, clean, and mate. This means that the Komodo National Park should create measures to limit the disturbance at these sites,” said Mr. Ande Kefi, an employee of the Komodo National Park involved with this study. “I hope that this study will encourage tourism operators to understand the need for the regulations already imposed and increase compliance.”

Despite Indonesia’s history with intensive manta ray fisheries, Komodo National Park still retains large manta ray aggregations that with careful ongoing management and threat reduction will benefit regional manta ray populations. The study highlights marine protected areas that are large enough to host important manta ray habitats are a beneficial tool for manta ray conservation.

To sum up, this long-term study reveals the following key observations:

- Komodo National Park is an essential habitat for manta rays.

- Surveyed sites are used differently by adults and immature individuals.

- A combination of cleaning, reproductive and foraging behaviours was observed among mature mantas, with immature individuals mainly observed foraging.

- Injuries from fisheries were readily observed and by-catch in corridors outside the MPAs will continue to add pressure.

- Tourism use of the manta sites has increased and needs to be managed carefully.

The authors of the study recommend limiting the number of tourism boats allowed at one time at manta ray aggregation sites and making mandatory codes of conduct for diving and snorkeling with manta rays.

The data for this 5-year long study was obtained from citizen scientists and trained observers submitting ID photos to the global manta ray database, www.mantamatcher.org. 1,085 reef manta rays were identified from 3,941 sightings that occurred between 2013 – 2018 based on their unique ventral coloration patterns.

This research was supported by the Australian Postgraduate Award & Murdoch International Top Up (EG), Dive Operators Community of Komodo, Ocean Park Conservation Foundation, Foundation FortUna, Mantahari Oceancare, Fish-Are-Friends, SeaMorgens, Arenui, R. Horner, and other private donors.