As you’re probably aware, the ‘Great Eight’ are our Great Barrier Reef’s living icons – the creatures at the top of everyone’s ‘must see’ list when they visit the Reef.

But they are also a reflection of the diversity of life on the Reef. They range from mammals to fish, reptiles to molluscs and they all procreate in very different ways. The Humpback whale for example, travels to our Reef specifically to mate and a year later, give birth. Likewise, turtles return in adult life to lay their eggs in the same sand dunes from which they first hatched decades earlier. So let’s have a fascinating look into how the Great Eight procreate.

(Before anyone gets too excited: there are no images of anything copulating in this blog – this is a GA rated website).

Whales

The most commonly sighted whales along our Great Barrier Reef are humpback whales and dwarf minke whales, with the annual cycle of the humpback whale being relatively well documented: during Australia’s winter, from June to September, up to 10,000 whales migrate north from Antarctica’s colder waters to the warm shallows of the Reef to breed and, the following season, give birth.

Now whales are mammals, and despite the fact that they live their entire lives in water, they breathe air, and have pretty much the same tackle as we do when it comes down to it. The mating process is also very similar to that of humans: it usually starts with a song, (humpbacks have the longest and loudest songs), then there’s a bit of argy-bargy between the males (the ‘bulls’), and finally one male establishes ‘dominance’. The actual act per se is performed much as it is with humans, though obviously under water, with the male on top.

The gestation period is about 11½ months, during which time the ‘cow’ humpback swims all the way back to the Antarctic to fuel up on krill before returning again the following season to give birth on our Great Barrier Reef.

A new-born humpback whale calf weighs about 1 tonne and drinks 500 litres of its mother’s milk every day, (which is so fat-rich, it’s the consistency of toothpaste) adding 4kg of weigh every hour. The calf needs to grow a thick layer of blubber as quickly as possible before it starts the long journey back to Antarctica.

The mother humpback continues to nurture the infant for a few years. This mode of reproduction produces few offspring, but increases the survival probability of each one.

You can swim with humpback whales in Hervey Bay and they are sometimes spotted while diving off Lady Elliot Island. Each year both Mike Ball Dive Expeditions and Spirit of Freedom run special Minke Whale Expeditions in June and July.

Giant Clams

Moving right to the other end of the ecological spectrum, the giant clam is the world’s largest species of mollusc. This animal – for yes it is an animal – comprises two hard shells which protect soft tissue inside which simply filters nutrients from seawater. It also gets some further nutrients from the bacteria living inside its tissue. Living to more than 100 years old, an adult giant clam can weigh around 200kg and stand almost a metre high. (Note the Seastar for scale).

So apart from the fact it looks like some kind of over-sized sexual organ, first question – are there boy clams and girl clams? Well, yes there are – but all clams start out as males. Like just about every living thing, the secret to survival is to grow quickly. Small clams, like small fish, put all their energy into growing. Only when they get to a certain size do they start to think (btw – a mollusc does not have a brain), about reproduction. But sperm requires much less effort to create than eggs. So small clams contribute the sperm.

Only when they grow past a certain size, and therefore age, do they ‘mature’ into females capable of producing eggs.

In terms of the actual reproduction, with giant clams there’s definitely no argy-bargy, but something in the water that triggers ‘group sex’. On some kind of signal, all the clams in the area release their eggs or sperm – or whatever they’ve got handy – into the water to maximise the chances of fertilisation. The largest giant clams, Tridacna gigas, can release more than 500 million eggs in one go.

After fertilisation, the cells rapidly divide and grow to a small ball of cells the size of a mulberry, then to free swimming larvae that feed on plankton. After a few weeks they settle in one place and start the serious business of growing up.

Hence, giant clams are found along the whole length of the Reef, and as the algae that provides extra nutrition to the clams requires sunlight, most can be seen on shallow reefs. Keep a lookout for their bright blue-brown mantle when snorkelling, but beware, they close their shells very quickly if they feel something nearby – so approach carefully if you want to see them in their full glory.

Manta Rays

Manta rays are among the largest fish in the ocean, growing to 7m from wing tip to wing tip and have the largest brain to body size ratio of any living fish. They are intelligent and curious, very aware of what’s around them and have been known to seek help from divers if they have become entangled in disused fishing gear.

This is all the more surprising as they are completely self-taught: at birth they are simply popped out – miniature replicas of their mother – and left completely to their own devices.

Further, manta sex takes place not long after birth! Confused? – Let’s go back to the beginning.

Mantas spend a bit of time at cleaning stations. Female mantas spend much more time than males, and males, it seems, go mainly to stake out females. Certainly, when a receptive female – often a heavily pregnant female – is encountered, males start to follow her around like a bad smell, hoping to be next in line once she becomes ‘available’. This can be shortly after she have given birth. (In the best-observed scenario of a captive manta, she became pregnant within hours of giving birth).

In the wild, the males line up behind the female who leads them all on a merry dance, twisting and turning through the ocean trying to throw them off: a sight referred to as a manta love train. Eventually, when she has whittled her suitors down to just one, he is permitted to mate. In another rather tortuous ordeal, he has to grab her left wing tip in his mouth, managing to hold one via a row of tiny teeth, which appear to have this sole purpose (mantas being filter feeders). The mantas finally arrange themselves belly to belly for copulation which takes a few minutes.

Manta rays reproduce via aplacental viviparity, meaning they give birth to live young which are hatched from an egg inside the female’s uterus. The pup, which is wrapped in a thin membranous egg case, hatches inside the mother’s oviduct and then feeds on the mother’s uterine milk until they are fully developed and ready to be born. At which stage – the cycle starts again.

On the Reef, the best place to see a manta ray is on a reef or cay close to the edge of the continental shelf, such as Lady Elliot Island. Find out more about mantas’ complex courtship love train here.

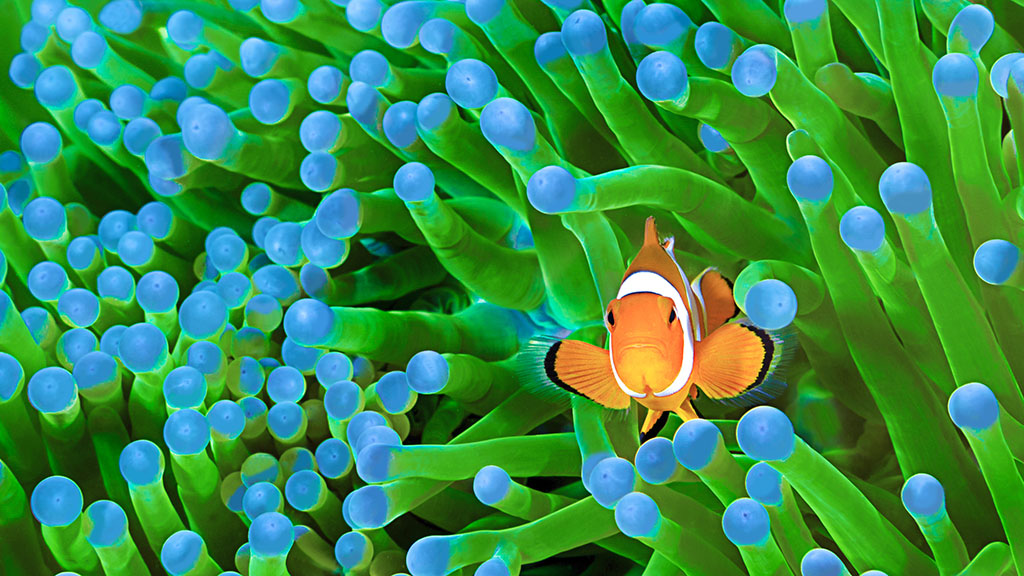

Clownfish

Clownfish – or more correctly anemonefish – share a unique symbiotic relationship with sea anemones. They are immune to the sting in the anemone’s tentacles, which provides them with a safe haven from predators. In return for this safe haven, the clownfish help the anemone by attracting other fish and shrimp, which get stung and eaten by the anemone.

So how would you describe the sex life of a clownfish? Let’s just say it’s complicated…

The female clownfish is always at the top of a clownfish colony hierarchy. When she dies, the most dominant male changes sex to replace her. This means of course, that Nemo’s dad, Marlin, should really have been his mum.

Once the eggs, which are laid very close to, or even under the sea anemone, have been fertilised by the male, it is the male that is responsible for looking after them. Indeed, he spends up to 2 weeks fanning the eggs to help they develop.

Turtles

Six of the world’s seven species of sea turtles are found in the waters around our Great Barrier Reef with the green turtle being the most common. It’s really quite strange that we find turtles so endearing, as they are actually just cold blooded reptiles: they breathe air, but live in water, and so have to come onto dry land to lay their eggs.

So when, where and mainly how do these armour plated reptiles get it on? Hands up anyone who has any idea?

By some still little understood method, pregnant female turtles return to the beach where they first hatched to lay their own eggs. Obviously, male turtles have worked this out, and hang out around the beaches regularly use around mating season. But how do they all know when it’s mating season? Temperature!

The temperature has to be just right. Warmer eggs produce female hatchlings, and cooler eggs produce male hatchlings and to get a nice mixed brood of kids – the temperature has to be just right.

So the males hang out waiting for the females and when they turn up they simply mount on top of them and hold onto the front of the female’s carapace. It’s a sort of rear entry job – we’ll leave it at that, but in order to prevent other turtles having a go, a male could hang on in there for up to 24 hours! This is both selfish and unnecessary, as the female turtle needs to mate with many males to fertilise the several clutches of eggs she will lay in the one season.

So that’s what happens next, the female hauls herself up the beach, digs a hole and lays up to a 100 eggs in a clutch before covering it over and dragging herself back down into the water, only to return a couple of weeks later to repeat the process over again.

On our Reef, Turtles lay their eggs from October onwards, and from December onwards, you can see the turtle hatchlings scampering down the beach to the ocean. Only one in a thousand make it, but those that do can live up to a hundred years old.

Sharks

Our Great Barrier Reef is home to a great variety of sharks, ranging from small, bottom-dwelling sharks, like wobbegongs, to larger types, like tiger, hammerhead and even the biggest shark of all – the whale shark. Around the reefs themselves, the most commonly seen sharks, are not surprisingly, the reef sharks – the black-tipped, white-tipped and grey reef sharks.

Most fish lay eggs, which are then fertilised, but though sharks are fish, reef sharks give birth to fully formed, live swimming young.

So what’s shark-sex like? It’s a pretty rough affair – especially for the females. In common with mantas, the male has claspers, one of which needs to be inserted into the female for a few minutes. But to do that, the male needs to get a purchase – so how do you think he does that? By a generous amorous bite around the gill area. Ouch!

Another downside of shark sex is the fact that, unable to swim whilst interlocked, the two sharks fall through the water column often coming to rest on the seabed, and as they are not swimming, their gills are not able to draw any oxygen from the water. So they are effectively holding their breath through the entire intercourse!

Interestingly, some sharks have the ability to store the sperm and use it up to a year or so later, if conditions for pregnancy are not optimal immediately after mating. Gestation periods vary by shark and can be anything between 6 and 13 months. They finally give birth to multiple pups – up to hundred – at a time. But, if it gets a bit crowed in there meantime, pups have been known to devour their siblings.

Potato Cod

The Potato Cod is a native Australian fish, and belongs to the Groper family. Gropers are among the largest of all bony fish and can be quite serious predators. The Potato Cod’s cousin, the Queensland Groper, or giant grouper, is the largest bony fish found on our Reef, and known to grow to more than 2m long and weigh up to 400kg.

There are about 500 species of Groper – and they’re all a bunch of gender benders. It is both true, and also, a deliberate survival strategy.

All groupers are born girls. At some point in their lives, they become boys. The transition is usually related to age and size and works to ensure there are enough members of each sex to come to the party when it’s time to get on down.

The reproductive process is another case of ‘group sex’. During an aggregation and spawning event, usually triggered by something like a full moon, the females release their eggs in open water, and the mates release sperm. Camera pans to full moon, and nature takes care of the rest. And actually, if you’re a 400kg bony fish – this is probably the safest way to have sex!

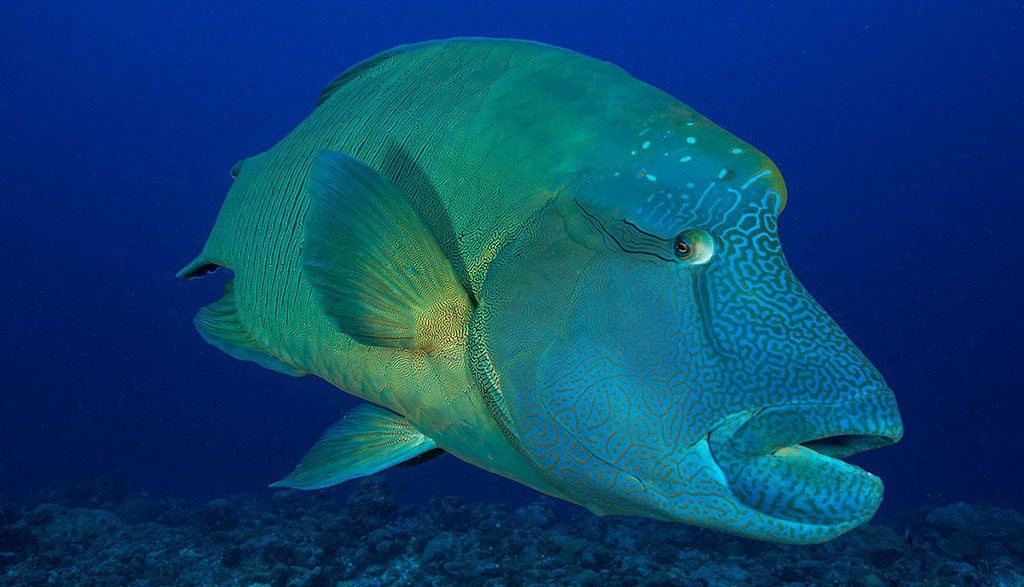

Maori Wrasse

The Maori Wrasse – also known as the Humphead Wrasse or even the Napoleon is the largest living member of the wrasse family. Easily identified by its large size, thick lips, and the hump that appears on the forehead of larger adults.

If you were hoping we’d left the juiciest fish-sex until last, I’m afraid you’ll be disappointed. Does this friendly guy look like he has a kinky sex life – I think not! The Humphead wrasses, like the Groupers, are protogynous hermaphrodites, (which means they have both sets of ‘tackle’ – though usually one set is predominant at any particular time), with some female members of a population becoming male at about 9 years old.

With Maori Wrasse preferring to live singly, and aggregations events being infrequent, often large males will approach and hang out with divers and snorkelers simply because they’ve become a bit bored of their own company.

When they do aggregate for the purposes of procreation, it’s the usual ‘spray and pray’ method employed by most fish.

If there’s one thing I hope you’ve learned from this blog – it is that small marine creatures expend most of their energy becoming big marine creatures. Big marine creatures can then put all their energy into reproduction – in an exponential way. Little fish can lay 100s of eggs, but big fish can lay 100,000s.

Once we’ve consumed all the big fish, it will take a very long time for fish stocks to recover, and if we continue to catch smaller and small fish of the one species – they may never recover. Treat eating fish like a luxury, and eat sustainably caught and certified wherever you can.